This interview cost Suzan Crane 200 rupees and a couple of sweet lassis. Nothing comes for free when dealing with the Gypsies. Some call them cheats. Others appreciate the fabled legacy of these artistically gifted and long-persecuted nomads. (Originally published in Untamed Travel – October 2005.)

Supari is beautiful and exotic. Long black hair frames hypnotic dark eyes and a beguiling smile that reveals gold-flecked teeth. She may be 20, but is not sure as there are no birth records. She is poor as the dirt on which her family lives in tents outside the holy city of Pushkar in Rajasthan, India. “All gypsy people very poor,” she says in English. “When we work, we get food. No work, no food. Only sitting.”

Supari is beautiful and exotic. Long black hair frames hypnotic dark eyes and a beguiling smile that reveals gold-flecked teeth. She may be 20, but is not sure as there are no birth records. She is poor as the dirt on which her family lives in tents outside the holy city of Pushkar in Rajasthan, India. “All gypsy people very poor,” she says in English. “When we work, we get food. No work, no food. Only sitting.”

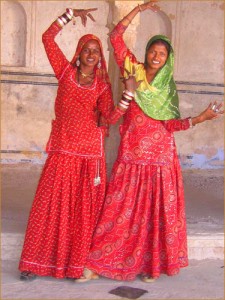

Nathori, her niece, is around the same age and equally exquisite. They wear vibrant floor-length dresses and head scarves and are fully bejeweled: silver glimmering on fingers, ears, and around their necks, wrists and ankles. Nathori sports a traditional jhumra and muter, an ornate headpiece connected to chandelier-shaped earrings. Each boasts small tattoos on hands or arms which will often also be embellished with elaborate henna designs. “We think very beautiful,” Nathori says.

Supari and Nathori are Kalbeliya Gypsies, known as the “snake-charmer caste” and amongst the lowest class of people in India. They are illiterate and live on the fringes of society as squatters in a village called Ganahera with about 100 other Kalbeliya who relocated from the Jaisalmer desert to capitalise on the fertile tourist trade of Pushkar. “Before I move like donkey. I put my things on donkey and sit,” says Supari of her journey to Pushkar. Today, as semi-nomads, the girls are more likely to travel by foot or rickshaw.

Kalbeliya women are renowned for their dancing and singing (the men for their musical prowess) and each day the girls trek the mile into town to perform or teach gypsy dance to tourists. Until recently, Pushkar was teeming with Gypsies selling hand-made beaded jewelry, cajoling foreigners into over-priced henna designs, playing music for money, or begging. Because of an unfortunate incident involving a Western man, extortion, and the police, most Kalbeliya have been expelled from the tourist Mecca.

Gypsies – or Roma people – originated from Rajasthan’s Thar Desert and began migrating West some 1,000 years ago. (There are approximately one million assimilated Roma people living in the U.S.). Traditionally nomadic, Gypsies possess a rich heritage of music and dance which has influenced many Western art forms ranging from Spanish flamenco to contemporary groups such as the Gypsy Kings. Once they performed for kings and maharajas. Now, the Roma, having suffered centuries of discrimination, perform on the street for spare change. Almost annihilated by the Nazis, they are still reviled and victimised in India and Europe. “Sometimes Indian people will spit on us or chase us away,” Sapori moans.

Gypsies – or Roma people – originated from Rajasthan’s Thar Desert and began migrating West some 1,000 years ago. (There are approximately one million assimilated Roma people living in the U.S.). Traditionally nomadic, Gypsies possess a rich heritage of music and dance which has influenced many Western art forms ranging from Spanish flamenco to contemporary groups such as the Gypsy Kings. Once they performed for kings and maharajas. Now, the Roma, having suffered centuries of discrimination, perform on the street for spare change. Almost annihilated by the Nazis, they are still reviled and victimised in India and Europe. “Sometimes Indian people will spit on us or chase us away,” Sapori moans.

But the Roma people – particularly the Kalbeliya – retain a fierce pride and struggle to maintain their culture and identity. “We sometimes argue, but our family and group are the most important things to us,” Nathori says.

Supari and Nathori are both unmarried, but their husbands have already been chosen by their fathers or older brothers. The potential grooms are snake-charmers, considered an important occupation as the cobra is the manifestation of Lord Shiva. Neither girl has ever spoken to her future spouse, but, as dictated by tradition, the boy will live with the girl’s family for a year before marriage as a sort of test run or “half marriage”. Nathori will wed in several months, her niece in about two years. “Gypsy girl cannot choose her own husband. It is not possible, so we just hope boy is nice, treats us nice,” Nathori says.

Supari adds: “Sometimes boys will drink, maybe get angry against us. But this does not happen so often.” While it is often assumed that Gypsy girls are looking for a ticket out, neither would consider marrying outside of her caste. “I have some foreign men friends. Sometimes they help me, but they are just my friend,” Supari insists.

According to custom, the brides wear red and cry throughout the ceremony because she is leaving her family to become the husband’s property. Ten days of festivities and rituals will surround the event but, contrary to the usual Hindu practice, the man’s family will pay for the wedding and dowry. Each girl will give birth within the first year or she will be considered “no good” as a wife.

Supari has two older brothers and four sisters. Both her parents are dead. Nathori has one brother and two sisters. Her mother is also dead and her father “works for baksheesh” as a sadhu, a Hindu holy man. But Nathori’s father is not really a sadhu; he just dons the garb to make money.

Their lives are simple. In the morning the girls walk 10 minutes to retrieve water which they carry back in pots on their heads. After sunset and the evening meal of chapati and dal – which is the same as the morning meal – they lie around on rusty metal beds “doing nothing” or dance while the younger ones watch and learn. All Kalebilya women dance but not all perform. Sometimes Supari and Nathori will take the 45-minute bus ride to Ajmer to catch a Bollywood film, which they enjoy for “the good dancing and singing”.

Their lives are simple. In the morning the girls walk 10 minutes to retrieve water which they carry back in pots on their heads. After sunset and the evening meal of chapati and dal – which is the same as the morning meal – they lie around on rusty metal beds “doing nothing” or dance while the younger ones watch and learn. All Kalebilya women dance but not all perform. Sometimes Supari and Nathori will take the 45-minute bus ride to Ajmer to catch a Bollywood film, which they enjoy for “the good dancing and singing”.

They speak several languages, including Hindi, their native Kalebilyan tongue and a bit of English. They are Hindus and go to the temple while their “Gypsy God is dancing,” but do not veil their faces like many Indian women. With an occasional cigarette dangling from their lips, they will joke about sex in their own language and laugh about the “loose and unstable, crazy foreigners.” Kalebilya women would never wear Western clothing because “short clothes and pants not possible for us. Too much problem. Would seem we’re not good girls,” Nathori explains.

And they are good girls, who adhere to strict codes of moral propriety. Sex before marriage is unlikely while ‘Western concepts’ such as having fun or planning for the future are incomprehensible. “We dance, we make marriage, we have babies,” Supari says. For them, there is daily survival and obedience to traditions. Gypsy women, like other Indian women, are limited by caste and circumstances.

And they are good girls, who adhere to strict codes of moral propriety. Sex before marriage is unlikely while ‘Western concepts’ such as having fun or planning for the future are incomprehensible. “We dance, we make marriage, we have babies,” Supari says. For them, there is daily survival and obedience to traditions. Gypsy women, like other Indian women, are limited by caste and circumstances.

Some day the girls may get to the West to perform. Many people have invited them, but securing passports is difficult without birth certificates or identification cards. In the meantime, Supari and Nathori will continue to dance and seduce foreign tourists with their innately flirtatious manners, garnering a rupee here, a rupee there, a cup of chai or a samosa. Sometimes a new dress or jewelry – never enough jewelry – will be presented as gifts.

And when time steals their beauty, they, like other Kalbeliya women have done for centuries, will resort to begging.

Global Gypsy Collection ©2010 - 2011

Global Gypsy Collection ©2010 - 2011