Suzan Crane journeys through the wetlands, forests and mountains of one of SE Asia’s last great hideouts for nature and wildlife. En route she stays in a longhouse with some of the few remaining hunters and gatherers and gets caught in an elephant stampede. (Originally published as At Home with the Headhunters in KLM Airline’s inflight Holland Herald, February 2005. DOWNLOAD)

I am hot, sweaty and itching like a dog with fleas. The insidious little creatures known as sand flies have marked their territory on every inch of my body. Slipping and sliding down steep muddy embankments, progress impeded by fallen trees and the aggressive attacks of prickly skinned bushes, we venture deep into the bowels of Malaysian Borneo’s primeval rainforest.

I am hot, sweaty and itching like a dog with fleas. The insidious little creatures known as sand flies have marked their territory on every inch of my body. Slipping and sliding down steep muddy embankments, progress impeded by fallen trees and the aggressive attacks of prickly skinned bushes, we venture deep into the bowels of Malaysian Borneo’s primeval rainforest.

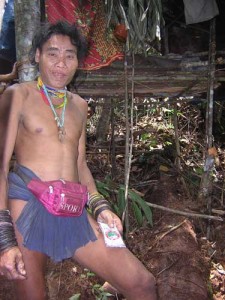

“I take you to a hidden paradise,” Jok, my Kayan driver, says as we walk further into the bush. Then I see them, barely visible amidst the dense jungle foliage: several primitive dwellings constructed of ragged tree branches and torn bark welded together by thin strips of rattan.

Intentionally eschewing the well-trodden tourist track I have collided with an extraordinary parallel universe.

Curious eyes and toothless smiles greet our arrival at the camp of this small group of Penan nomads, the most remote of Sarawak’s 27 indigenous tribes and amongst the last remaining hunter-gatherers on earth. In an archaic world where time has no meaning and people don’t know their age, daily life consists of simply finding food: blowpipes with poison darts to hunt wild boar, monkeys and mouse deer; bamboo baskets to collect sago, their dietary staple.

Dirty-faced toddlers wearing beaded bracelets around their spindly legs peer out from behind loin-clothed men and topless women while elders puff on banana leaf-wrapped cigarettes. A cooking fire is burning in one of the open-sided lean-tos where pet monkeys are tethered. According to custom I present the chief with smoking tobacco, a well-received gift. It quickly dawns on me that I am in the presence of a dying civilisation. Imperiled by globalisation and deforestation, the survival of these illiterate peripatetic Orang Ulu (“Upriver People”) is tenuous. An estimated 40 percent of this dwindling tribe has resettled in housing provided by the government.

With more than 45 dialects spoken in Sarawak communication is limited to smiles and gestures. Regardless, I am grateful that I made the 350km, four-wheel drive journey over dusty logging roads to visit these elusive drifters. That night is spent on the floor of a Penan family’s one-room (sans electricity) wooden hut. We prepare our evening meal on the banks of the river, paddle across it to retrieve fresh spring water and do our morning ablutions in the privacy of the bushes.

My excursion through Malaysian Borneo started several weeks earlier in Kuching, the historic, heterogeneous capital of Sarawak, Malaysia’s largest state and one of three that comprise the island of Borneo (Sabah lies to the north and Indonesia’s Kalimantan to the south; Brunei is a sultanate). Upon arriving, visions of Borneo as an untamed frontier quickly evaporated. The world’s third largest island is a study in contrasts where contemporary urban sensibilities fuse with tradition. KFC and Starbucks vie for space amongst local markets and heritage sites, vendors wearing Nirvana T-shirts hawk durian and dried fish, and young people leave their rural longhouses for opportunities in the cities. Customs such as ancestor worship persist, but many Dayak (Iban and Bidayuh) have combined their animistic beliefs with Christianity.

My excursion through Malaysian Borneo started several weeks earlier in Kuching, the historic, heterogeneous capital of Sarawak, Malaysia’s largest state and one of three that comprise the island of Borneo (Sabah lies to the north and Indonesia’s Kalimantan to the south; Brunei is a sultanate). Upon arriving, visions of Borneo as an untamed frontier quickly evaporated. The world’s third largest island is a study in contrasts where contemporary urban sensibilities fuse with tradition. KFC and Starbucks vie for space amongst local markets and heritage sites, vendors wearing Nirvana T-shirts hawk durian and dried fish, and young people leave their rural longhouses for opportunities in the cities. Customs such as ancestor worship persist, but many Dayak (Iban and Bidayuh) have combined their animistic beliefs with Christianity.

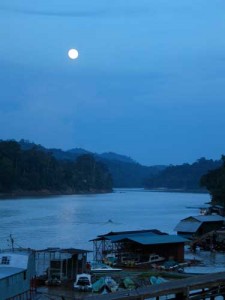

Kuching is charming, but I’m eager to head upriver. Nine hours, two boats and few Westerners later we land in Kapit, the “gateway” to the upper Rejang and Baleh Rivers (the latter providing the backdrop to Redmond O’Hanon’s travel classic Into The Heart Of Borneo). A vibrant port town where local tribes converge, we arrive during the annual Kapit Fest. Underscoring Sarawak’s cultural cacophony, tattooed Iban and Kayan people peddle larvae and homegrown produce in the market followed by traditional tribal performances in the town square. It is here that we meet Mr. Philip and secure an invitation to his wife’s remote Iban longhouse, a communal society unique to Borneo’s indigenous groups.

The road is unfinished and smells of wet tar. It threads through a wooded interior scarred by the Iban’s slash-and-burn paddy fields. A year ago this secluded area was accessible only by longboat, a four to six hour journey from Kapit. The end of the road feels like the end of the earth. Precariously balancing our loaded backpacks, we negotiate a clear shallow stream, the cool water dancing around our knees – and a welcome reprieve from the incessant tropical heat. Up rickety wooden stairs to our hosts waiting on the veranda above, the perfume of the forest commingles with the strong scent of burning plants.

We are ushered inside and drop our packs in the vast common area known as the “living room”. A phalanx of kids scurry out from behind closed doors like mice scampering out of their holes, reticent smiles pasted on their faces. Small groups of women sit together weaving and preparing vegetables for sale in the market. Squares of natural rubber dry in the sun, as roosters crow outside. Several elders join our party. Most do not speak English.

After partaking of the customary welcome drink tuak – fermented rice wine – we bathe in the translucent river clad in sarongs. Later we trek through a rocky creek enveloped by thick jungle to harvest vegetables from the small plot of land belonging to the family. Our hostess Ngana picks leafy greens and corn. She then throws a few ears on the fire that has been started to keep the mosquitoes at bay. Dinner that night consists of vegetables and rice, chicken, deer and python, which my friend Ian describes as “chewy and surprisingly boney”. Although not on the menu, the locals also feast on a variety of insects, including cicadas and grasshoppers, fried or steamed in leaves. After dinner we meander through the 22-door longhouse, which houses a like number of families. Looking skyward we are greeted by mummified trophies of the community’s ancestors: several groupings of heads encased in bamboo “cages” hang in front of doors. Once a year the descendants of Sarawak’s largest and most fearsome headhunting tribe make ritualistic offerings to the heads for good luck.

After partaking of the customary welcome drink tuak – fermented rice wine – we bathe in the translucent river clad in sarongs. Later we trek through a rocky creek enveloped by thick jungle to harvest vegetables from the small plot of land belonging to the family. Our hostess Ngana picks leafy greens and corn. She then throws a few ears on the fire that has been started to keep the mosquitoes at bay. Dinner that night consists of vegetables and rice, chicken, deer and python, which my friend Ian describes as “chewy and surprisingly boney”. Although not on the menu, the locals also feast on a variety of insects, including cicadas and grasshoppers, fried or steamed in leaves. After dinner we meander through the 22-door longhouse, which houses a like number of families. Looking skyward we are greeted by mummified trophies of the community’s ancestors: several groupings of heads encased in bamboo “cages” hang in front of doors. Once a year the descendants of Sarawak’s largest and most fearsome headhunting tribe make ritualistic offerings to the heads for good luck.

That night, we sleep under mosquito netting in the front room with our host family. When we awake at sunrise most of the residents of the longhouse are already out.

Then we take another long journey to Miri, the northernmost city of Sarawak. An overnight stop at a modern Kayan longhouse in Long Bidian precedes my visit with the Penan. Here I meet old women, who as adolescents stretched their ears and tattooed their arms, hands, legs and feet as means of “beautification”. Kelabit women sport different images on their appendages, believing tattoos are beacons that “glow like mushrooms in the jungle and lead them to those who died before,” explains Hendrick Nicholas, a Kelabit artist.

From there, it’s off to the recently anointed World Heritage Site of Mulu National Park – noted for adventure caving and its fabled “Headhunter’s Trail” – and then onto Sabah.

Nicknamed “The Land Below the Wind,” Sabah was formerly known as North Borneo and passed through many ruling hands before joining Malaysia in 1963. Its preponderance of natural resources has long been exploited by palm-oil plantation owners, land barons and logging industrialists and parts of Malaysia’s poorest state are still under dispute by neighbouring Indonesia and the Philippines. Unlike Sarawak, Sabah’s sense of history and culture is muted. Although an astounding 80 dialects are spoken, its indigenous peoples melt inconspicuously into an ethnic pot of Malay, Chinese, Indonesians and Filipinos.

Nicknamed “The Land Below the Wind,” Sabah was formerly known as North Borneo and passed through many ruling hands before joining Malaysia in 1963. Its preponderance of natural resources has long been exploited by palm-oil plantation owners, land barons and logging industrialists and parts of Malaysia’s poorest state are still under dispute by neighbouring Indonesia and the Philippines. Unlike Sarawak, Sabah’s sense of history and culture is muted. Although an astounding 80 dialects are spoken, its indigenous peoples melt inconspicuously into an ethnic pot of Malay, Chinese, Indonesians and Filipinos.

Sitting on the edge of the South China Sea’s turquoise waters overlooking coral-fringed islands and the towering Crocker Range, the skies are crying again today in Kota Kinabalu, Sabah’s capital. It’s rainy season and at least once a day a downpour blankets alaysian Borneo.

A local bus drops me in the little town of Gum Gum from where we are transported to the Sepilok Orangutan Rehabilitation Center and the fertile Sungai Kinabatangan floodplain. I spend the next several days at Uncle Tan’s wildlife camp where we lodge in rudimentary cabins, with mattresses on the floor, shrouded in mosquito netting. Uncle Tan’s is one of several establishments dotting the Sungai Kinabatangan that offer wildlife “safaris”. A few provide more luxurious accommodations, but none, I’m sure, provides glimpses into more varied wildlife. Lan, the head guide, can spot a camouflaged tree frog with his trained eye as easily as I can find a good sale on shoes. Many people extend the basic three-day/two-night package, often staying for weeks on end in the relaxed family-atmosphere nurtured by the local staff.

But there are moments of danger, too. Like when we’re trekking through the mangrove-laden jungle and encounter a small band of pygmy elephants. Spooked by our proximity, they chase us. “Help,” I shriek in a tiny voice as I tumble into a ditch, with the elephants in hot pursuit.

But in the end, we make it out down to the riverbank and they back off. Back at camp, however, we find that some stealthy macaques have stolen our daypacks from our door-less stilt huts and food from the kitchen. The resident bearded pigs are wallowing in mud pools while a massive lizard languishes nearby.

During our nocturnal river safaris, the glowing eyes of crocodiles peer up from inky water which mirrors the starry sky. Wild cats skulk through the low grass of the wetlands while owls and kingfishers perch on branches above. Endangered proboscis monkeys swing high atop the trees, otters scurry near the riverbank and hornbills soar overhead. Traversing the jungle on foot, we come across scorpions, snakes, bats, giant centipedes, luminous butterflies, frogs and hordes of spiders creeping through the darkness.

Begrudgingly, I leave the serenity of Uncle Tan’s for Sipidan, a small island renowned for spectacular marine life. Just metres below the aquamarine waters of the Celebes Sea, a kaleidoscope of colours and patterns jump-start the senses. Enormous turtles appear to fly through the underwater universe while tropical fish cruise calmly by. Sipidan is amongst the world’s most legendary dive spots, but even with snorkel and fins the vista down under is superb.

The small city of Semporna is not much more than a link to Sipidan and a stop off for the citizenship-less Sea Gypsies – the aquatic equivalent to Sarawak’s Penan nomads – who roam the waters off the coast. But on this day of Hari Raya, which marks the end of the Muslim holy month of Ramadan, the mood is festive. Praying and singing at the nearby mosque has been audible throughout the night and everyone is bedecked in finery. Not a good day to travel, I discover. With buses running sporadically, I must rely on an extortionist Chinese taxi driver to get me to the airport for my return flight to Kota Kinabalu. With memories etched indelibly in my mind I consider my experiences on this bountiful island where – despite travel advisories – I always felt secure in the warm embrace of its gracious inhabitants. “The people take you into their hearts and families without hesitation,” says an Australian tourist named Maxine Thomas, echoing the sentiment of most travelers I meet.

Malaysian Borneo’s cities are sometimes dirty. Its rainforests have been raped. Its politics are dubious. However, despite copious eco-treasures and adventure options – caving, trekking, rafting, climbing, mountain biking and diving – it has yet to be paved over by full-throttle commercialization.

Malaysian Borneo beckoned to me once. I suspect it will call again.

BEAUTY MARKS

Our hostess, Jega Anak Keling (Jega, the child of Keling), leans down beside me. “They want to know if you are a man or a woman,” she chuckles. Now I’m no Pamela Anderson, but I’m fairly certain that my gender is apparent. “It’s because you have a tattoo on your chest,” she explains. In Iban society only men tattoo the chest. The women adorn their arms. Using carbon from a kerosene lamp, tattoos – particularly the customary depiction of brinjal flowers on a man’s upper torso – are executed by hand with a bamboo apparatus. Tattoos on the throat – applied when a boy is about 15 – and later on the back (believed to frighten the animals in the jungle) are signs of a warrior and a way to lure the ladies. “If a man didn’t have tattoos, a woman wouldn’t fall in love with him,” I am told. For women, tattoos signify rank and skill. Only the elders still don conventional designs as young people prefer contemporary body art. The same holds true for the traditional ear stretching of Kayan and other Orang Ulu clans where women once used brass weights to lengthen their earlobes. Today, even the elders have surgically cut the lobes back.

Our hostess, Jega Anak Keling (Jega, the child of Keling), leans down beside me. “They want to know if you are a man or a woman,” she chuckles. Now I’m no Pamela Anderson, but I’m fairly certain that my gender is apparent. “It’s because you have a tattoo on your chest,” she explains. In Iban society only men tattoo the chest. The women adorn their arms. Using carbon from a kerosene lamp, tattoos – particularly the customary depiction of brinjal flowers on a man’s upper torso – are executed by hand with a bamboo apparatus. Tattoos on the throat – applied when a boy is about 15 – and later on the back (believed to frighten the animals in the jungle) are signs of a warrior and a way to lure the ladies. “If a man didn’t have tattoos, a woman wouldn’t fall in love with him,” I am told. For women, tattoos signify rank and skill. Only the elders still don conventional designs as young people prefer contemporary body art. The same holds true for the traditional ear stretching of Kayan and other Orang Ulu clans where women once used brass weights to lengthen their earlobes. Today, even the elders have surgically cut the lobes back.

Global Gypsy Collection ©2010 - 2011

Global Gypsy Collection ©2010 - 2011